|

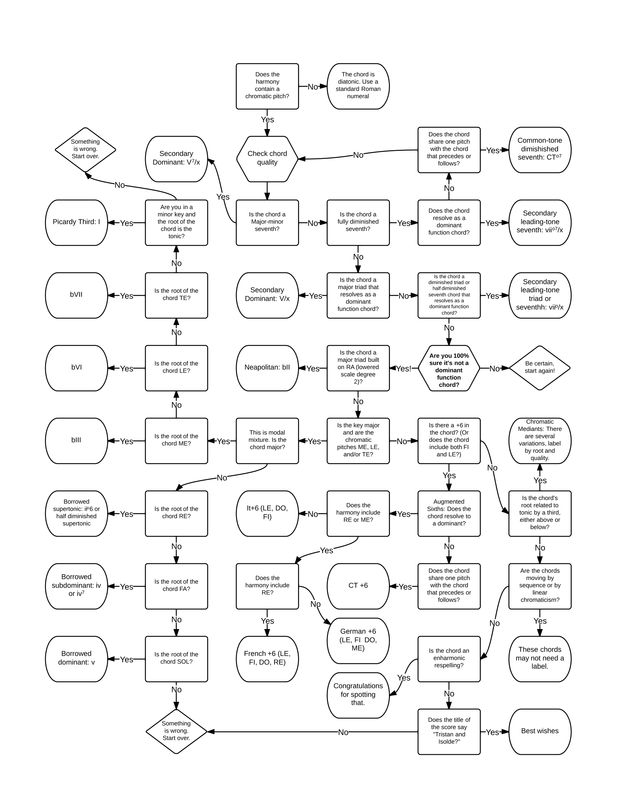

A few years ago I created a flowchart to help my second year music theory students decipher chromatic harmony. It's by needs a bit simplistic and certainly not exhaustive (e.g. it doesn't address popular harmony nor does it help for extensions past the seventh), but I think it's a good start and has been a useful tool for my students in moments when they just can't seem to find an answer. Feel free to download a .pdf version for your own use! Note that the flowchart uses "movable do" solfege to identify scale degrees, something that I find helpful when teaching concepts involving modal mixture.

When asked to write a paper in a music theory class, remember that the course focuses on the structures of music and your writing should reflect this emphasis. With that in mind, examine the following excerpt from a fictional student paper: “In measure 23 the music makes me feel as if I’m flying away to far-away lands filled with magic and mystery. This section reminds me of dancing unicorns and whimsical fairies playing in meadows of rainbow flowers.” This passage, while a bit exaggerated is a good example of several problems that are often encountered in first papers for music theory: It is not only far too fanciful and metaphorical, it is NOT ABOUT MUSIC! The focus should not be the listener’s emotional or imaginative response to the music but rather the structures that might evoke that response. Here is one potential re-write: “The virtuosic sixteenth note arpeggios in measures 23-30 evoke the sensation of flight before subsiding into a repetitive dance-like rhythmic motive in measure 31 that emphasizes this section’s compound meter.” The re-write preserves some of the metaphor (flight) but presents it within the context of specific musical structures. Always avoid providing “program” to the music when there is not a story explicit to the work. The next problem typical of student papers is that they can often become a musical “play-by-play” that serves as nothing more than a list of musical events as they occur without any explanation or interpretation. Here is a good example: “In measure one the subject is introduced in C minor. In measure 2 the subject modulates to G minor and it is a tonal answer. In measure 2 the countersubject also enters for the first time. Measures 4 and 5 are a sequence that modulates back to C minor.” This is nothing more than a robotic regurgitation of the facts. It is not analysis, it is identification. Here is an actual (edited) student example that is a bit closer to course expectations: “It is clear with the pauses in the alto voice that the piece is about to conclude and the pause in measure 28 supports this feeling. The terminative function is further made clear with the added voices and tonic pedal in measures 30-31 that makes the passage sound more polished and conclusive.” While not a perfect piece of prose it does strike a good balance between providing facts and identifying structures and providing the reader with an interpretation of what those structures mean for the music. Here is another example from a student paper: “Measure 11 contains a G7 chord which would be analyzed as V7/IV. This then resolves to a C chord (the tonic triad in the subdominant key) and repeats this pattern two beats later. This modulation is subtle and difficult to notice in the recording, but when tonic shifts back to the original key with a D7 chord it causes tension for the listener until its resolution in G two measures later.” This isn’t a bad bit of musical analysis. The only criticism is that the reader probably needs at least one more measure number to identify where the shift back to the original tonic occurs. Another common student problem is an over reliance on historical background to fill pages and word counts. It is useful to provide your listener with some basic historical background to help provide context for the music, but it is unnecessary to provide biographical information. Here is a good excerpt from an actual student introduction that is perfectly clear and to the point: “Johann Sebastian Bach was one of the most famous composers of the Baroque era. He is considered to be a master of the fugue because he wrote them in such an intelligent way. Bach published two volumes titled The Well-Tempered Clavier. These books contain a set of preludes and fugues in every key. The first volume was publish in 1722 and the second in 1744.” You should assume as a writer that any audience interested in a paper about a fugue is probably aware of Bach’s stature as “one of the most famous composers of the Baroque era” and would not require a reminder! Any more information about Bach’s background of the history of the Well-Tempered Clavier would be more appropriate for a paper in a music history course rather than one in music theory.

The best way to avoid many of these problems is to focus on a single unifying feature of each piece, section, or passage (depending on how long the paper.) Avoid generalizations about structures and instead provide a few examples of musical structures that tie together to provide explanation for any conclusions. For example, it is good to know that the middle section of a small ternary ends in measure 32 but what marks the conclusion? How does the music change to provide contrast and to help the listener and performer know that something new is happening? Was it the cadence, the texture, the dynamic, the melody, the harmony, the key or a combination of these and other musical phenomena? Explain to the reader, in specific musical terms, the logic that led you to make analytical decisions. The final and most difficult step of writing that A+ paper is finding a unique common thread in the music that you can tie together and present in a way that is engaging and informative. You should formulate a hypothesis about the music and then base your efforts on providing support for that point of view. This is what makes for interesting analysis and is how you get an A! For example, a paper that writes about the repeated use of a descending chromatic stepwise motion in the principle motive and then points out that the composer modulated to the Neapolitan as a large-scale reflection of this motive would be insightful and show that the student has spent time learning the structures of the piece before attempting to write about it. This should be your goal! |

|||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed