|

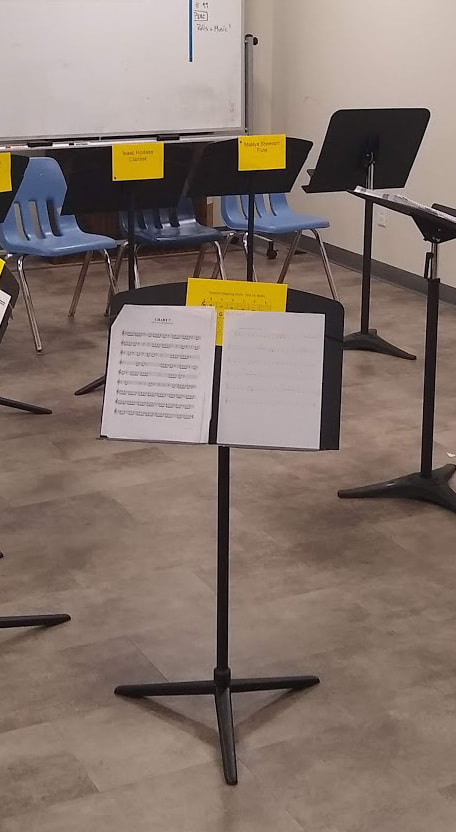

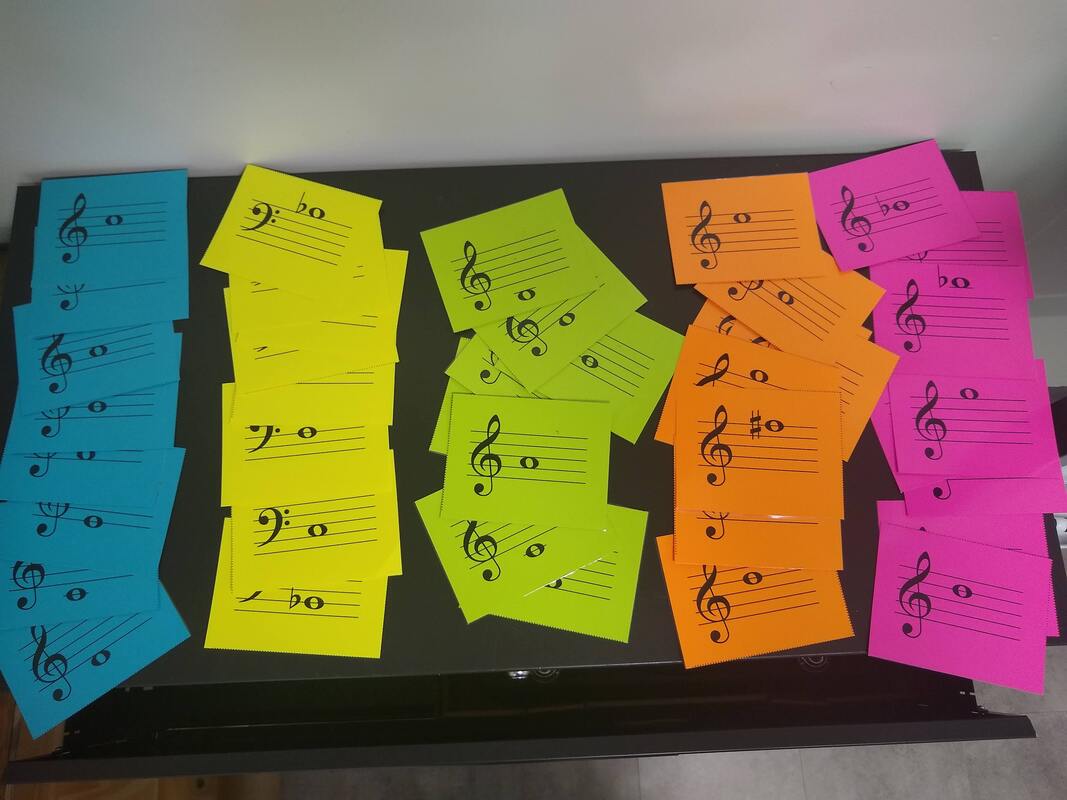

This is the Word File for the stand tags that I use. I actually created them on Mac Pages, so you may have to tweak things a bit to get them formatted correctly. The picture is an older image and the first iteration of them used scale degrees numbers instead of solfege, but this gives you a sense of what they look like, color coded by pull-out/class.

0 Comments

Technology has always driven humanity forward. Whether it was the discovery of agriculture and sanitation in the ancient world that allowed man to build cities or the development of the microprocessor that ultimately led to the internet revolution, our progress has been tied to the invention and use of tools. In his popular book Guns Germs and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (1997) Jared Diamond points to the use of tools as the moment that modern humanity began:

“Human history at last took off around 50,000 years ago, at the time of what I have termed the Great Leap Forward. The earliest definite signs of that leap come from East African sites with standardized stone tools and the first preserved jewelry (ostrich-shell beads). Similar developments soon appear in Near East and in Southeastern Europe, then (some 40,000 years ago) in southwestern Europe, where abundant artifacts are associated with fully modern skeletons of people termed Cro-Magnon. Thereafter, the garbage preserved at archaeological sites becomes more and more interesting and leaves no doubt that we are dealing with biologically and behaviorally modern humans.” (Diamond, 1997, p. 39).

We have moved far beyond stone tools, but the technological tools at the fingertips of modern humans are dizzying in both their scope and utility, as well as the rapidity of new developments. Technology simplifies and enriches nearly all aspects of our lives and ironically makes it possible, for the first time since the formation of cities, for humans to disperse again and yet still maintain our connectedness and the spread of knowledge.

The development of Western Music has been driven by technology as well. Several years ago, composer Howard Goodall hosted a televisions series titled “Big Bangs” in which he discussed the major inventions and developments in music history and how they pushed the art form forward. The first of five episodes covered Guido D'Arezzo and the development of music notation, but other topics that were covered include the invention of opera, the piano, equal temperament, and recorded sound. We can point to each of these moments, and many more as crucial moments in the history of music.

Like nearly all human domains, music has played a large role in the development of education and pedagogical practices. In the past 40 years, the introduction of computers to our schools has created a desire to incorporate digital technology in all aspects of education. (For me personally, my first introduction to computers in school was through the gifted program at my elementary school in the early 1980's. We were introduced to the BASIC programming language on the TRS-80 computer and learned how to code very simple programs.) Unfortunately, this has most often resulted in teachers and schools using technology because it exists rather than incorporating as a tool to meet learning outcomes.

"Technology use is often not commonplace. When it is used, it is frequently not integrated in a way that optimizes its potential to support learning, and perhaps to even transform the learning experience of students through innovative pedagogical approaches and the study of unique content" (Bauer, 2014, p. 6).

It is clear that the use of technology in schools has not kept pace with the explosion of technology outside of the classroom. Perhaps teachers rely on what they know and understand and resist change, or perhaps they simply do not see an effective and efficient way to use technology that is accessible for all of their students and their contexts.

"When making decisions about whether or not to use a particular technology, teachers should conduct a cost/benefit analysis that considers the technology's affordances (benefits) and constraints (limiting features) in relation to learning outcomes and the classroom context. Technology approaches shouldn't be used for technology's sake. They should only be incorporated when there is a clear benefit to learning" (Bauer, 2020, p. 8).

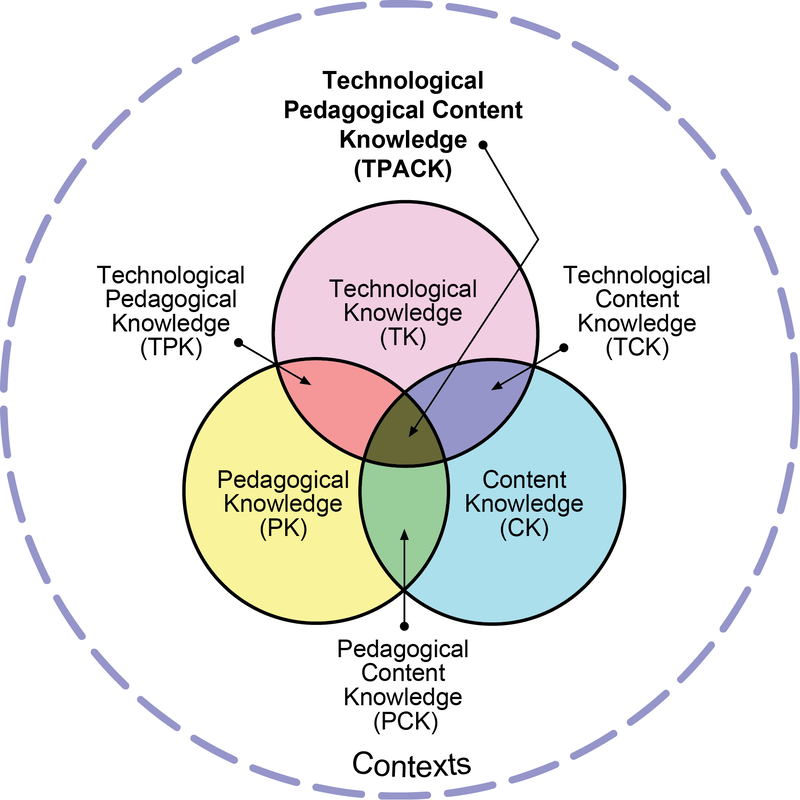

This problem has been studied by several researchers, most notably Schulman (1986) and Mishra and Koehler (2006). The latter proposed a framework for thinking about the use of technology and how it interacts with content area knowledge and pedagogical practice. The Technological Pedagogical and Content Knowledge (TPACK) model is a way to conceptualize the use of technology and make decisions about how to incorporate all three knowledge areas into teaching practice (Bauer, 2020).

In my own teaching, I have been forced by pandemic to embrace more technology into my own classroom. One example from my classroom that fits the TPACK model is the use of the Flipgrid with my elementary band students. For a recent assessment activity conducted via remote learning, I was able to record a pedagogical video for my instrumental students on Flipgrid. They were able to watch the video and ask questions before being required to provide a recording of themselves demonstrating the new skill. I was then able to provide feedback to them on their video and repeat the process as many times as needed. In this case, I was using the technology to meet my pedagogical goal and not for its own sake. I'm sure this is just one of countless examples of teachers finding new and innovative ways to deliver their content through technology.

The COVID-19 pandemic might be the figurative "big bang" that education needs to fully embrace and integrate technology in a more productive and student-centered way. Remote learning has forced teachers to confront the limitations and advantages of technology and find new and innovative ways to use the tools at hand to serve their student needs. One day we may look back on this moment as a turning point in education and the moment when we fully embraced the digital age and its many wonders in our classrooms. References: Bauer, W. I. (2020). Music learning today: Digital pedagogy for creating, performing, and responding to music. (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199890590.001.0001 Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: The fate of human societies. W. W. Norton & Company. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668790210001591614 Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00684.x Schulman, L.S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge in the growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2). http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X015002004 Looking for free flash cards for your beginner instrumentalists? Here are 4-Note and 8-Note Cards here for Flute, Clarinet, Alto Sax, Trumpet, Bells, Trombone/Euphonium, and Tuba.

I'd like to announce that I've finally launched my latest project, a new podcast where I interview teachers, composers, and performers of music for winds and percussion. The first episode is an interview with Cleveland area teacher and fellow composer John Pasternak. The conversation touches on John's early influences, his time as the arranger for the Kent State Marching Band, his publishing company JM Publishing, composing for band, and the importance of staying humble and approachable. Please give it a listen!

The direct link to the feed is http://everythingbandpodcast.libsyn.com/rss.

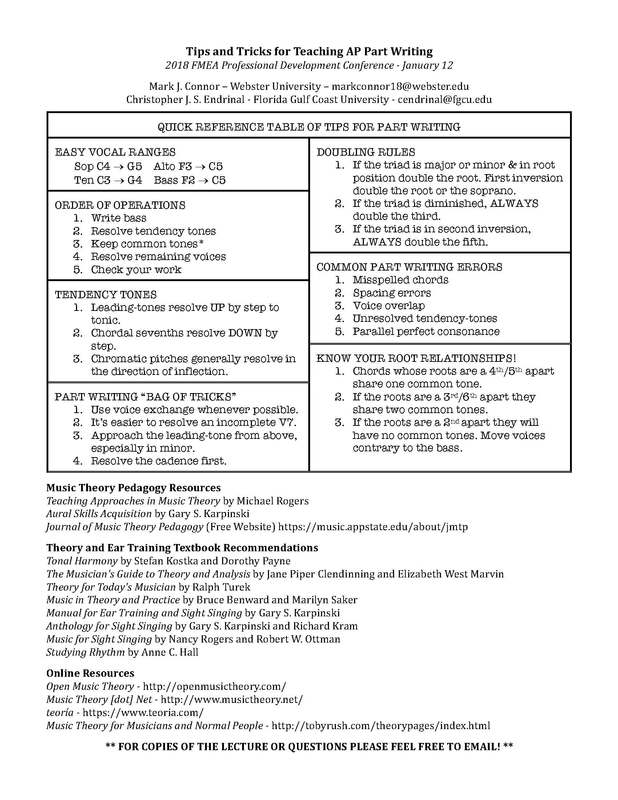

A few years ago I created a flowchart to help my second year music theory students decipher chromatic harmony. It's by needs a bit simplistic and certainly not exhaustive (e.g. it doesn't address popular harmony nor does it help for extensions past the seventh), but I think it's a good start and has been a useful tool for my students in moments when they just can't seem to find an answer. Feel free to download a .pdf version for your own use! Note that the flowchart uses "movable do" solfege to identify scale degrees, something that I find helpful when teaching concepts involving modal mixture.

When asked to write a paper in a music theory class, remember that the course focuses on the structures of music and your writing should reflect this emphasis. With that in mind, examine the following excerpt from a fictional student paper: “In measure 23 the music makes me feel as if I’m flying away to far-away lands filled with magic and mystery. This section reminds me of dancing unicorns and whimsical fairies playing in meadows of rainbow flowers.” This passage, while a bit exaggerated is a good example of several problems that are often encountered in first papers for music theory: It is not only far too fanciful and metaphorical, it is NOT ABOUT MUSIC! The focus should not be the listener’s emotional or imaginative response to the music but rather the structures that might evoke that response. Here is one potential re-write: “The virtuosic sixteenth note arpeggios in measures 23-30 evoke the sensation of flight before subsiding into a repetitive dance-like rhythmic motive in measure 31 that emphasizes this section’s compound meter.” The re-write preserves some of the metaphor (flight) but presents it within the context of specific musical structures. Always avoid providing “program” to the music when there is not a story explicit to the work. The next problem typical of student papers is that they can often become a musical “play-by-play” that serves as nothing more than a list of musical events as they occur without any explanation or interpretation. Here is a good example: “In measure one the subject is introduced in C minor. In measure 2 the subject modulates to G minor and it is a tonal answer. In measure 2 the countersubject also enters for the first time. Measures 4 and 5 are a sequence that modulates back to C minor.” This is nothing more than a robotic regurgitation of the facts. It is not analysis, it is identification. Here is an actual (edited) student example that is a bit closer to course expectations: “It is clear with the pauses in the alto voice that the piece is about to conclude and the pause in measure 28 supports this feeling. The terminative function is further made clear with the added voices and tonic pedal in measures 30-31 that makes the passage sound more polished and conclusive.” While not a perfect piece of prose it does strike a good balance between providing facts and identifying structures and providing the reader with an interpretation of what those structures mean for the music. Here is another example from a student paper: “Measure 11 contains a G7 chord which would be analyzed as V7/IV. This then resolves to a C chord (the tonic triad in the subdominant key) and repeats this pattern two beats later. This modulation is subtle and difficult to notice in the recording, but when tonic shifts back to the original key with a D7 chord it causes tension for the listener until its resolution in G two measures later.” This isn’t a bad bit of musical analysis. The only criticism is that the reader probably needs at least one more measure number to identify where the shift back to the original tonic occurs. Another common student problem is an over reliance on historical background to fill pages and word counts. It is useful to provide your listener with some basic historical background to help provide context for the music, but it is unnecessary to provide biographical information. Here is a good excerpt from an actual student introduction that is perfectly clear and to the point: “Johann Sebastian Bach was one of the most famous composers of the Baroque era. He is considered to be a master of the fugue because he wrote them in such an intelligent way. Bach published two volumes titled The Well-Tempered Clavier. These books contain a set of preludes and fugues in every key. The first volume was publish in 1722 and the second in 1744.” You should assume as a writer that any audience interested in a paper about a fugue is probably aware of Bach’s stature as “one of the most famous composers of the Baroque era” and would not require a reminder! Any more information about Bach’s background of the history of the Well-Tempered Clavier would be more appropriate for a paper in a music history course rather than one in music theory.

The best way to avoid many of these problems is to focus on a single unifying feature of each piece, section, or passage (depending on how long the paper.) Avoid generalizations about structures and instead provide a few examples of musical structures that tie together to provide explanation for any conclusions. For example, it is good to know that the middle section of a small ternary ends in measure 32 but what marks the conclusion? How does the music change to provide contrast and to help the listener and performer know that something new is happening? Was it the cadence, the texture, the dynamic, the melody, the harmony, the key or a combination of these and other musical phenomena? Explain to the reader, in specific musical terms, the logic that led you to make analytical decisions. The final and most difficult step of writing that A+ paper is finding a unique common thread in the music that you can tie together and present in a way that is engaging and informative. You should formulate a hypothesis about the music and then base your efforts on providing support for that point of view. This is what makes for interesting analysis and is how you get an A! For example, a paper that writes about the repeated use of a descending chromatic stepwise motion in the principle motive and then points out that the composer modulated to the Neapolitan as a large-scale reflection of this motive would be insightful and show that the student has spent time learning the structures of the piece before attempting to write about it. This should be your goal! (I had the opportunity today to answer a question on the music teachers Facebook group from a high school choir director asking for tips for teaching AP music theory. I'm going to paraphrase some of that response here.)

My first bit of advice was to peruse some of the more commonly used music theory textbooks to see which seems a good fit. While most textbooks appropriate for teaching undergraduate theory are similar, they do have some differences, especially in the amount of prose and the amount of contextual analysis and Schenkerian concepts they use. I currently use the Musician's Guide to Theory and Analysis by Clendinning/Marvin but I have also used, and liked textbooks by Ralph Turek, Kostka/Payne, and Benward/Saker. In the end, with enough experience teaching theory, there really is no need for a textbook and you can get by with a resource like the wonderful Open Music Theory and worksheets and exercises created yourself. For teaching aural skills, I'm a devotee of Gary Karpinski's pedagogical methods and thus highly recommend his Manual for Ear Training. There is an accompanying sight singing book that corresponds with the dictation text, but any set of melodies could be used. However, I do believe that you can probably teach the aural skills component of AP Music Theory without a textbook, though I personally wouldn't choose to do so. There are also several references that are invaluable sources for pedagogical advice. There are two books that are must reads for anyone who teaches music theory. The first is Michael Roger's venerable Teaching Approaches in Music Theory and Gary Karpinski's Aural Skills Acquisition. Another great resource is the Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy which has now been made FREE (!!) for anyone to download and read any of the multitude of articles that address virtually every topic in theory teaching. Finally, the College Board itself has study guides and curriculum guides available for all of its AP courses, including AP music theory. Careful study of that and a comparison with a textbook table of contents can possibly provide a good starting point for piecing together a curriculum.  I recently completed this really fun and interesting commission from the City of Troy Illinois for the Troy Community Band. The mayor, Allen Adomite (a former drum major) and the director John Malvin (his former teacher) put together the funding and I am honored to have given the city a unique piece of music. In an era where the arts need our support more than ever, it was very special to be a part of something where the music itself is valued by a local municipality and it's officials. The march will be premiered on July 22nd in Tri-Township Park in Troy as part of the Lion's Club 75th Troy Homecoming Celebration. It will follow the parade which begins around 6:30pm. For the past 10 years I've had the privilege of teaching, among other things, first semester music theory. Each fall semester I greet a new group of first-year music majors to my classroom with the assumption that they have very little background in music theory and fundamentals. As a result, the bulk of the fall semester is spent teaching the fundamentals of music before proceeding into two voice counterpoint and the heart of the undergraduate theory curriculum.

However, there are a few theory skills that I find to be extremely useful for incoming students. Some of these are pretty basic, which is precisely why they are on this list.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed